Enlarged Prostate or Prostate Cancer? Advances in Screening, Treatment and Preserving Quality of Life

Enlarged Prostate or Prostate Cancer? Advances in Screening, Treatment and Preserving Quality of Life

Prostate cancer is the most common type of cancer in men, with the exception of skin cancers caused by long-term exposure to the sun. One in eight men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their lifetime, but the majority of them will live with it, not die from it.

Still, most men are understandably reluctant to discuss the unwelcome possibility with their doctor that they are at risk for the disease or may even already have it. There is nothing to be gained, though, by avoiding the subject, says Dr. Douglas Scherr, Clinical Director of Urologic Oncology and Professor of Urology at Weill Cornell Medicine. In fact, you might be agreeably surprised by the many advances in screening, diagnosis and treatment of a disease that is no longer equated with a death sentence.

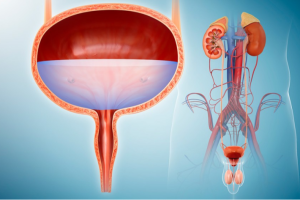

What Is the Prostate?

The prostate gland is better known for the problems it creates than what it actually does in a man’s body, says Dr. Scherr.

Located just below the bladder, the prostate plays a key role in male reproduction and fertility, producing the fluid that transports sperm.

As men age, the prostate tends to get larger—a condition called benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), which can interfere with the normal outflow of urine. “BPH may cause you to wake up several times a night to urinate,” says Dr. Scherr, “or you may feel like you can’t empty your bladder completely. Blood in the urine is yet another sign of BPH.”

The risk of developing prostate cancer increases with age as well. Dr. Jim Hu, a urologic oncologist, Professor of Urology and Director of the LeFrak Center for Robotic Surgery at Weill Cornell Medicine, names several other factors that raise a man’s prostate cancer risk:

- A family history of cancers, including mothers and sisters with early-onset breast, ovarian or uterine cancer

- African American race

- Higher body-mass index

- Exposure to Agent Orange, a tactical herbicide the U.S. military used during the Vietnam War. Veterans who were exposed to Agent Orange may have developed certain cancers or other illnesses.

However, BPH and prostate cancer are usually unrelated, Dr. Hu says: “An enlarged prostate does not mean a man will develop prostate cancer down the road.”

PSA screenings

To stay on top of their prostate health, men aged between 55 and 69 years old would be well advised to have a PSA test every 2 to 3 years. Men at higher risk should get screened during their 40s, giving their doctor a baseline number that will determine how often they’ll need to be tested in the future.

“If your number is less than 1, that generally means you have a low lifetime risk of prostate cancer,” says Dr. Hu. “If it’s greater than 1, we’ll monitor you more closely.”

Elevated PSA may indicate the presence of cancer, but it may also be a sign of BPH. “To distinguish between individuals whose elevated PSA is due to BPH and those whose results suggest cancer,” he says, “we order a prostate MRI.”

Early incorporation of MRI technology into the screening process has been transformative, he adds: “An MRI helps us avoid unnecessary biopsies if it shows nothing ‘suspicious,’ and it permits a more accurate biopsy by targeting any suspicious area.”

Dr. Timothy McClure, an attending urologist and Assistant Professor of both Urology and Radiology, notes that all three of these procedures—PSA testing, MRI and biopsy—can be performed during one visit. “We’ve streamlined the entire process,” he says. “There’s no need for multiple appointments, which is great news for patients.”

Treating an enlarged prostate

“We take BPH symptoms very seriously and treat it accordingly for two reasons: to improve a man’s quality of life and to prevent damage to the kidneys. Having difficulty urinating and walking around with a full bladder can cause kidney damage over time,” Dr. Hu says.

Treating BPH starts with medication, but if the condition fails to improve or worsens, surgery may be warranted. Today’s surgeons use advanced procedures such as laser therapy and aqua-ablation—a new treatment that uses high-powered water jets—to remove excess prostate tissue.

Another leading-edge treatment for BPH is prostate artery embolization, an outpatient procedure. Here’s how it works: “A tiny catheter is inserted through an artery in the leg or wrist and travels all the way down into the pelvis, ending up at the prostate artery,” Dr. McClure says. “There, tiny particles are injected into the artery. The procedure shrinks the prostate, making it much easier to empty your bladder. No surgery and no Foley catheter required.”

Treating low-to-medium risk prostate cancer

In decades past, we tended to overtreat prostate cancer, Dr. Hu says, “but now we take a more nuanced approach. Often, men with low-to-intermediate-risk disease can be safely followed with close monitoring, including annual PSA testing, a manual prostate exam and an MRI plus biopsy, if warranted.

Close monitoring, also known as active surveillance, is an established approach for low-risk prostate cancer patients, but there is always a chance that a patient’s cancer will progress. If it does, a wide range of advanced treatments are available to halt the disease in its tracks or even cure it altogether.

Surgical options

Traditional surgery is still used to remove a discrete tumor or even the entire prostate gland when absolutely necessary. However, says Dr. Scherr, a minimally invasive surgical treatment is now being used in some men with localized cancer. It’s called focal therapy. Surgeons perform the procedure by using MRI technology to identify the area of cancer that needs to be treated in the prostate. This then allows treatment with focal therapy to destroy only those parts of the prostate that are cancerous and leaves other tissues unharmed.

The goals of focal therapy are similar to those of traditional surgical procedures: to cure the cancer while preserving a man’s quality of life. That means preventing incontinence and maintaining sexual function. Focal therapy is fairly new, and the data are still inconclusive, Dr. Scherr says, but there are grounds for optimism on the part of surgeons and patients alike.

“Weill Cornell Medicine’s collaborative and interdisciplinary culture has fostered advances in focal therapy for prostate cancer. That culture is also what sets us apart from other insitutions,” says Dr. McClure, who practices medicine at the interface of urology, radiology and interventional radiology.